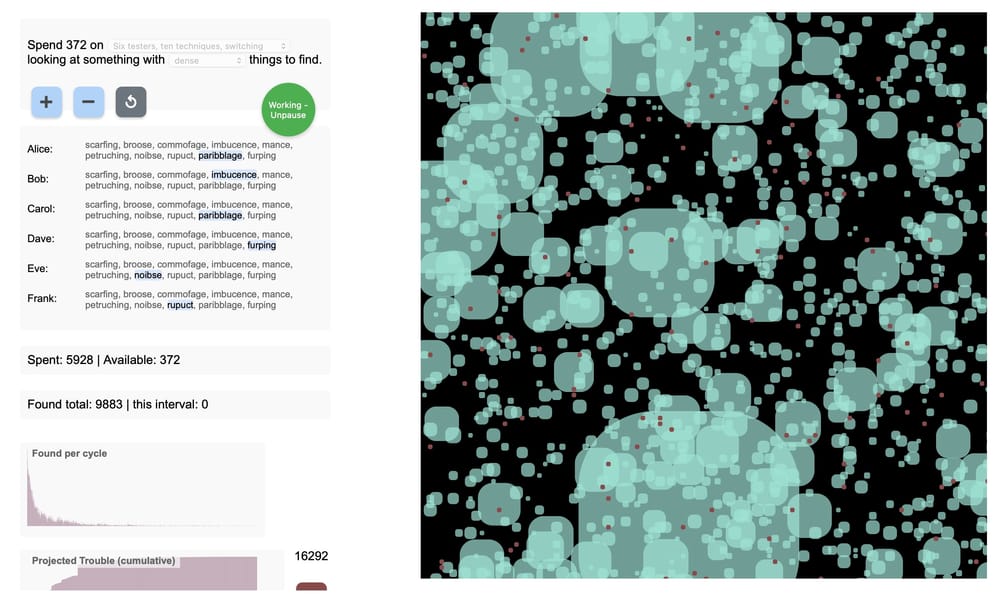

Exercise – Cost of Trouble

To be used in Workroom PlayTime012 on 17 April.

A 15-20 minute exploration via a simulation

Background

Based on an older exercise, no longer interactive, posts here: An Experiment with Probability, Broken Trucks, Models, lies and approximations, Enumeration hell, Diversity matters, and here's why, Modelling super powers . Go there to read background – I'll bring it here in the next few weeks and update it.

Each of these simulations have a similar core simplifications:

- the simulation knows what can be found, and it knows what's likely to find each thing, but the entities looking don't know either of these things.

- A searchable thing has a limited collection of independent things to be discovered. For testing, think: there are only so many problems.

- Discovery is by chance. Different approaches to searching have different chances. A discoverable thing has a low chance of being discovered by any individual approach – but might have a better chance by another approach. For testing, think: Performance testing will find different problems from usability testing.

- There's a limited budget – the more you spend, the more chances you have to find stuff.

- Something stays found, but only counts the first time it is found.

You, the user, can see and change the number of things that can be discovered, the makeup of the crew that looks for things, and the budget to spend looking. During the simulation, you can see the results of the simulation in terms of the work done, the discoveries found. You can pause and resume the work. You can increase and decrease the budget. Different simulations will throw up different results, and you'll want to keep track of those to see the variation.

Background: a simulation works in chunks. In each chunk, all the explorers have a chance to discover a (random) set of discoverables (of fixed size in the simulation). A discoverable's chance of discovery is set by the explorer's active skill, and the chance of the discoverable being discovered by that skill.

Priming Question

We'll come back to this in the debrief

Exercise 1: Variety of values

5 minutes playing and talking

Go to https://exercises.workroomprds.com/discoverysim/3/index.html.

In this simulation, the dots change colour and size when 'discovered'.

What can you say about the sizes in the simulation?

The size represents the value of the discovery. In testing terms it is perhaps the projected cost of the problem, if it had been found in production.

Exercise 2: Interpreting into testing

5 minutes mainly talking

What do you think about the 'value' of what one finds, when one finds a problem in testing?

Exercise 3: When to stop spending

5 mins playing and talking.

Let's all work with Ordinary – A in the "looking at something with X things to find' selection box..

Press the ⎋ button to remake your test subject – it'll keep the parameters from the simulation (JL except the budget - aargh!)

Press the ⏍ button to see the values of all the undiscovered things, all at once.

Run the simulation several times.

how do you feel about the budget, and what you're leaving uncovered?

* what can be found

* the value of finding those thing

You'll see what can be found by pressing the ⏍ button, in the text starting with 'secret' and in the Value of Trouble graph text.

The values in the B sets follow a "log normal" distribution. This can also have large, rare values, but doesn't show quite the wildness of a power law.

Both are common in nature, regularly identified in systems analysis and seem to be plausible distributions for the cost of software failure. In nature, the largest 'things' are often readily visible, or the distribution is limited by environmental factors. In bugs, the largest is often invisible and its cost can exceed the market capitalisation of the organisation which introduced the fault (think the crowdstrike problem in 2024)

I'll put links to the research when I feel confident that I've got readable sources.